As I believe I mentioned last post, it was pouring yesterday, which basically belayed what we were supposed to do on that day. But our Fearless Guide Rod was able to “smoosh” it all into one day – today!

We walked from the hotel over to the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. First, we visited the museum.

One of the most interesting “juxtapositions” was the “non-Māori” history, and the Māori history of New Zealand, side by side.

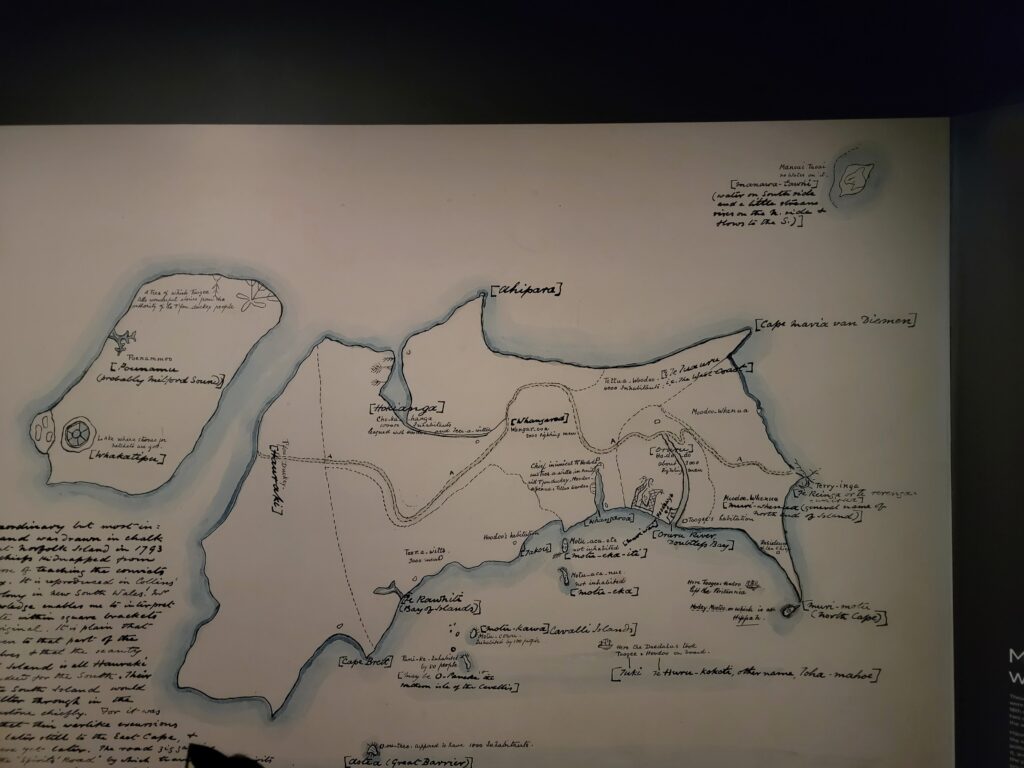

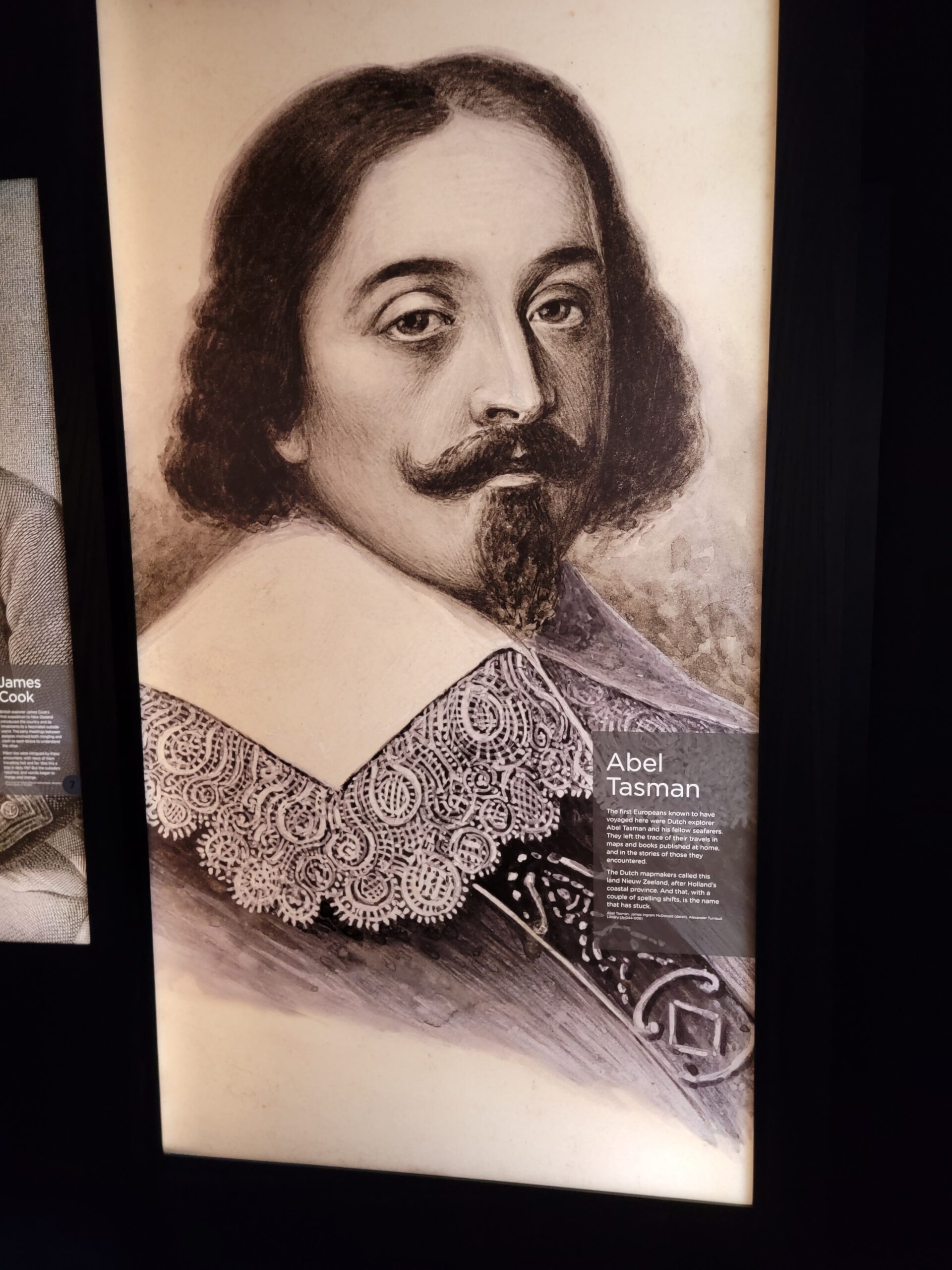

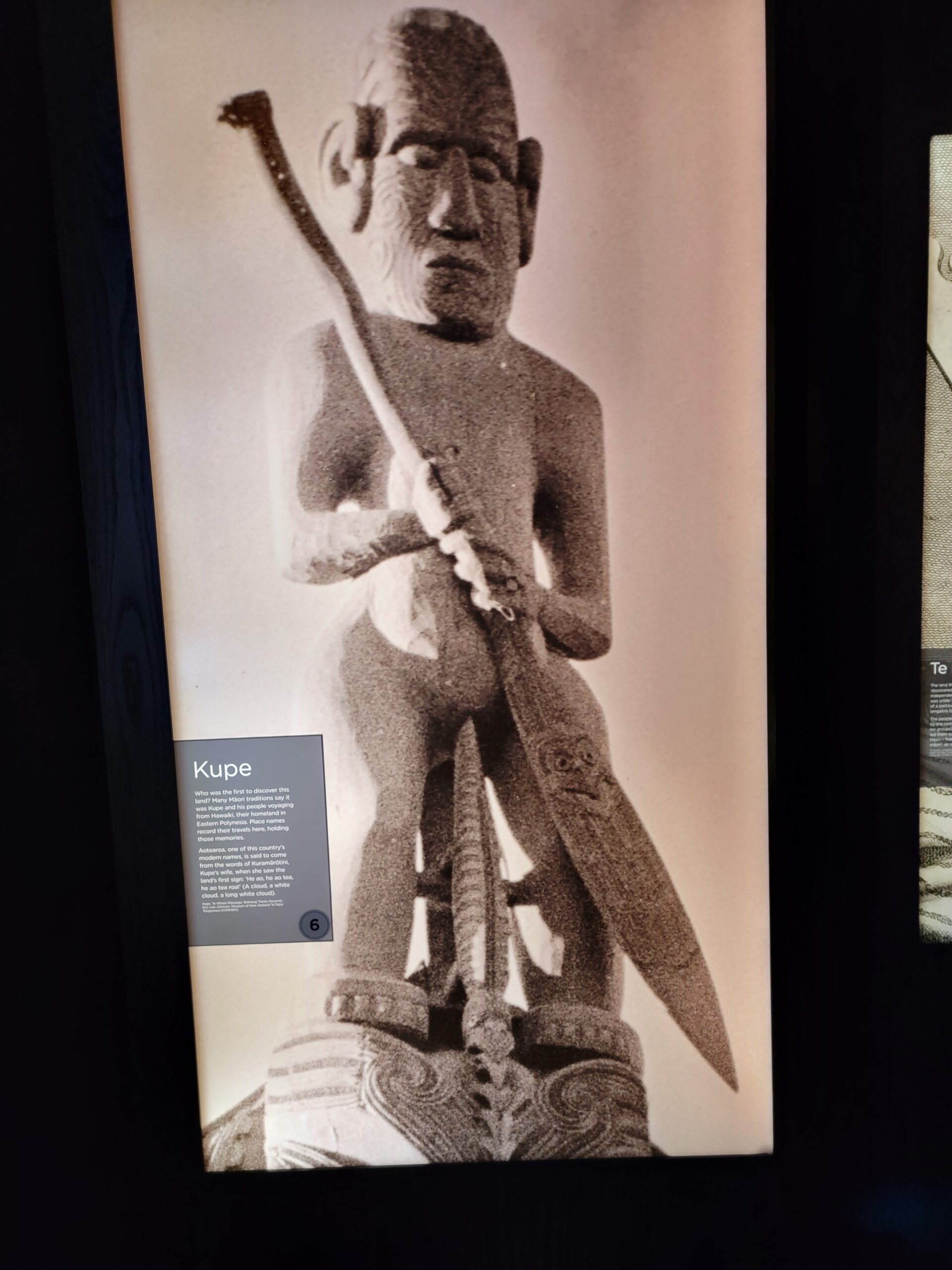

For example, above is Abel Tasman, the “discoverer” of New Zealand. He was Dutch, hence naming it after Holland’s coastal province (“Nieuw Zeeland”). Of course, he never actually landed on the shores (talked about that already). In juxtaposition, here is Kupe – Māori tradition is that Kupe and his people voyaged from Hawaiki, their homeland in Eastern Polynesia. Aotearoa, the country’s Māori name, is said to come from Kupe’s wife, Kuramarotini, when she first saw land. Apparently she cried: “He ao, he ao tea, he ao tea roa!” (“A cloud, a white cloud, a long white cloud!)

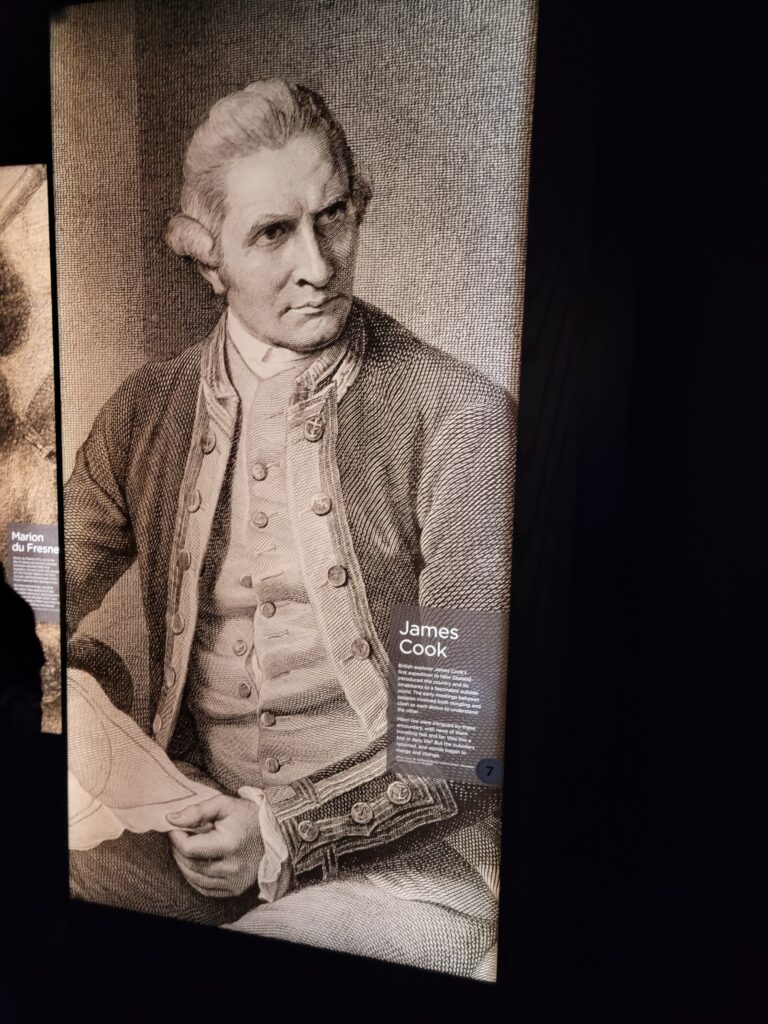

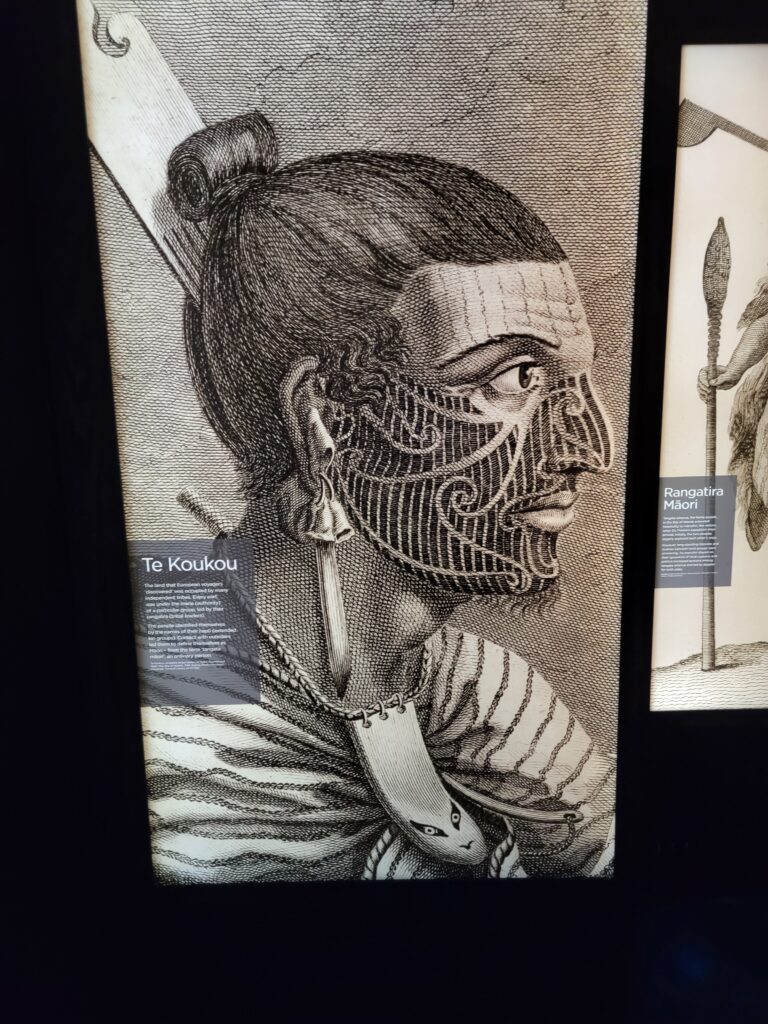

Here is another “juxtaposition.” This is Captain Cook. On the right is Te Koukou. The land that the Europeans “discovered” was occupied by many independent tribes. Every part was under the mana (authority) of a particular group, led by their rangatira (remember what that means? Tribal leader). The people identified themselves by the names of their hapu (extended kin groups). Contact with outsiders led them to define themselves collectively as “Māori,” from the term “tangata māori,” meaning “an ordinary person.”

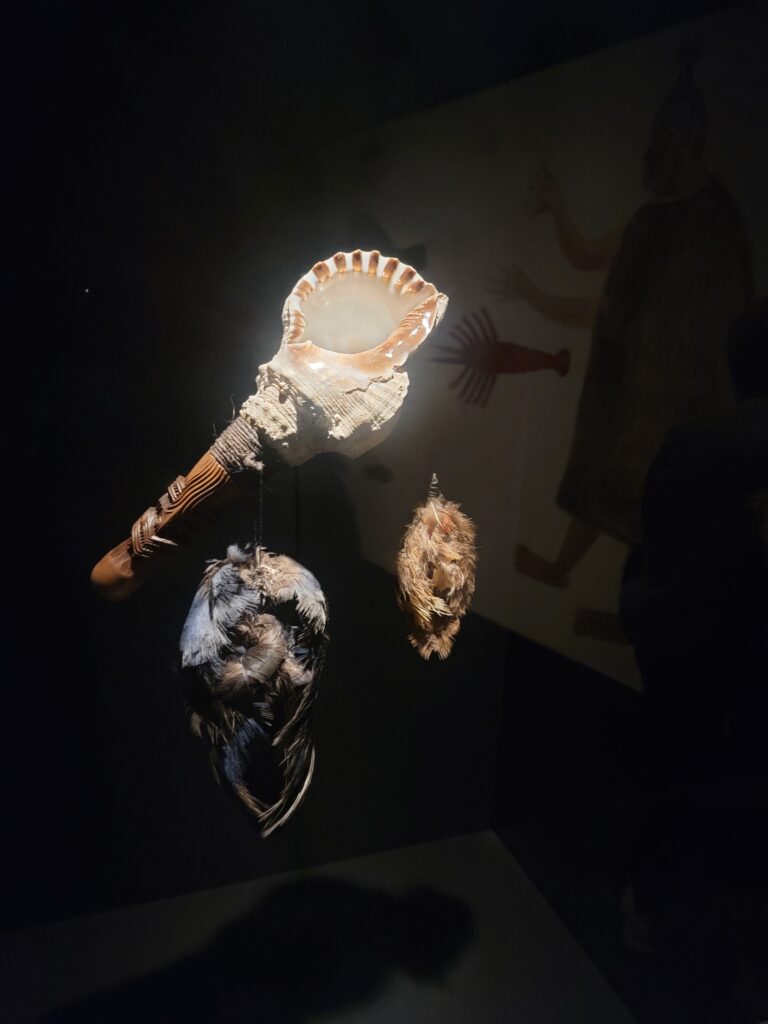

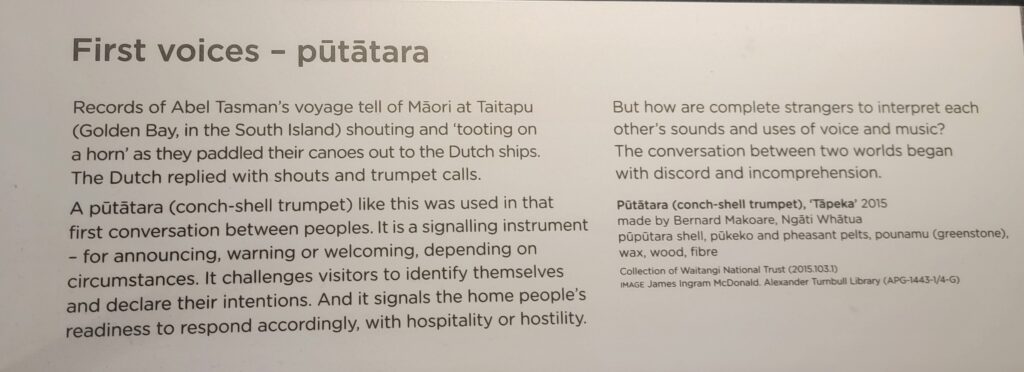

The above explains how things got off on the wrong foot. Not only did the “invaders” use trumpet calls that were interpreted as challenges, but they also paid zero attention to the Māori traditions of Tapu (“taboo”) such as areas that were not to be walked on, etc. This shows a Māori putatara at the left.

Once the bumbling Europeans (who said that?) started to somewhat integrate, as mentioned in a previous post. the Māori realized that they could be traders; they could also charge “license fees” for ships at anchor. (NOTE: Once they signed the Treaty, the ships stated that they paid this fee to the CROWN, not to the Māori. The tribes were VERY confused – as that was not how their version of the Treaty was written. More on that later!)

We had learned about trading during our tour the day before, but we uncovered at the museum that the biggest item of trade was Rope. The Europeans had an unending need for rope on their ships. One large naval ship might have 40 kilometers of rope rigging that would need to be replaced.

Philip King, Governor of the Norfolk Island prison colony, wanted the convicts to make rope from the flax growing there. He knew that the Māori had great expertise in this area. So – instead of paying the Maori to make the rope – you guessed it – he abducted two young Māori men.

Unfortunately, they didn’t know a thing about making rope, as it was “women’s work.” Interestingly though, King kept them on as they were hard workers, and ultimately they came home with pigs, potatoes, and vegetable seeds for their community – who shared with the next – and so on and so on.

Quick learners, the Maori started to have ships of their own (built in New Zealand to the “European” style). Unfortunately, they sailed one to Australia, and it was either blown out of the water or it was confiscated, because it wasn’t flying “a national flag.” That is what led to what is now called the “United Tribes of New Zealand” flag. (Remember, this was well before the Treaty of Waitangi).

There was a lot in the museum about the colonizers – French, English, etc. The U.S. sent a lot of trading ships to New Zealand, and they (of course, only a few years from their own independence) were very skeptical of discussions about whether New Zealand should be a colony. The English “promised” the indigenous tribes that they would protect them from the French, who were in “colonization” mode then as well. Apparently, the English made the better argument.

After visiting the museum, we were hooked up with our guide. The first thing he showed us was an enormous war canoe. It was taken out in 1983 when Prince Charles and Diana visited New Zealand to return the rangatira cape that had been presented to Queen Victoria. It is taken out once a year to celebrate the Treaty (don’t worry – it’s on tracks to get it down to the water!).

The warship was made of three enormous trees. The middle tree’s stump was still in evidence – Mark was kind enough to “model” how large around it was. The canoe is 84 meters (276 feet) long.

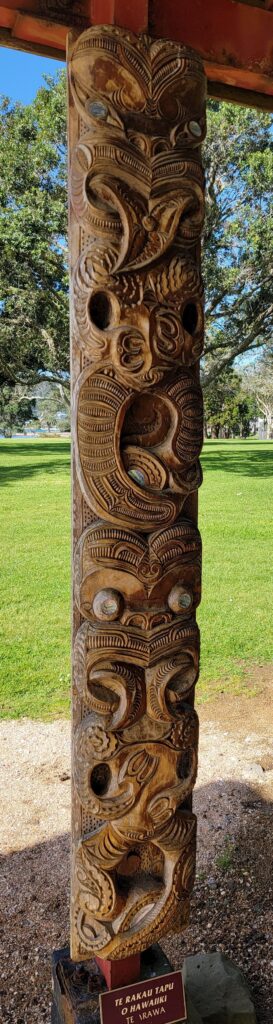

The “topknot” on a totem is very important. As Māori believe that the spirit enters through the fontanel, it represents the “silver thread” between Heaven and the individual. The head is the biggest portion of the totem because it’s the most important – all the senses “live” there.

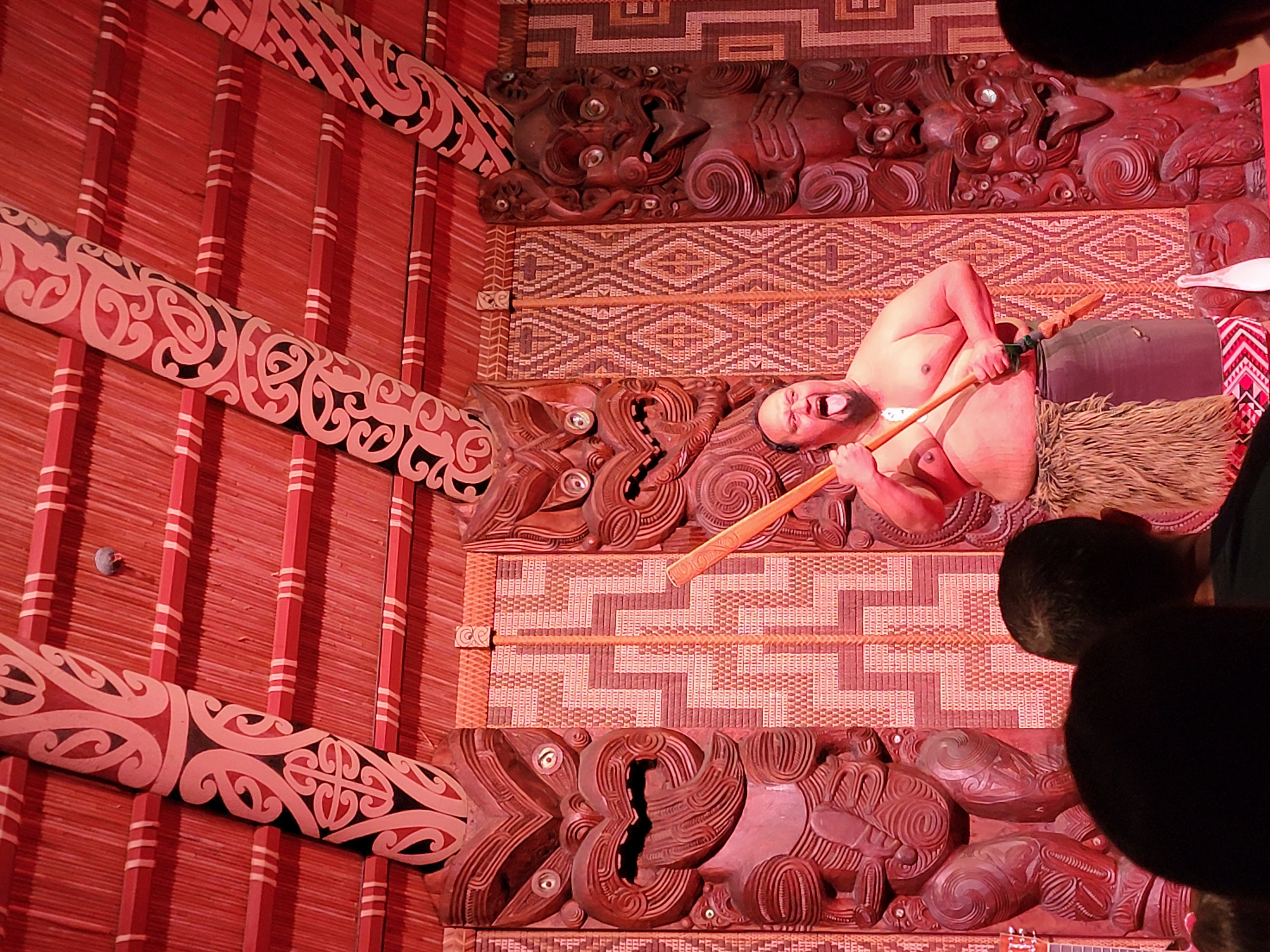

We also learned about the “tongues” of totems. If the tongue is sticking out straight, it can be a “true teller,” but it can also be a challenge (like in the haka, where both men and women bug their eyes out; women jut their chin whereas men stick out their tongue). If the tongue is right facing, that represents more of a “spiritual” totem – left facing represents more of a “business” totem (can also be warlike). If the tongue is split it’s a liar OR . . . politician!

From here we headed up to the top of the hill – where the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. We passed a tree that Queen Elizabeth had planted in 1953.

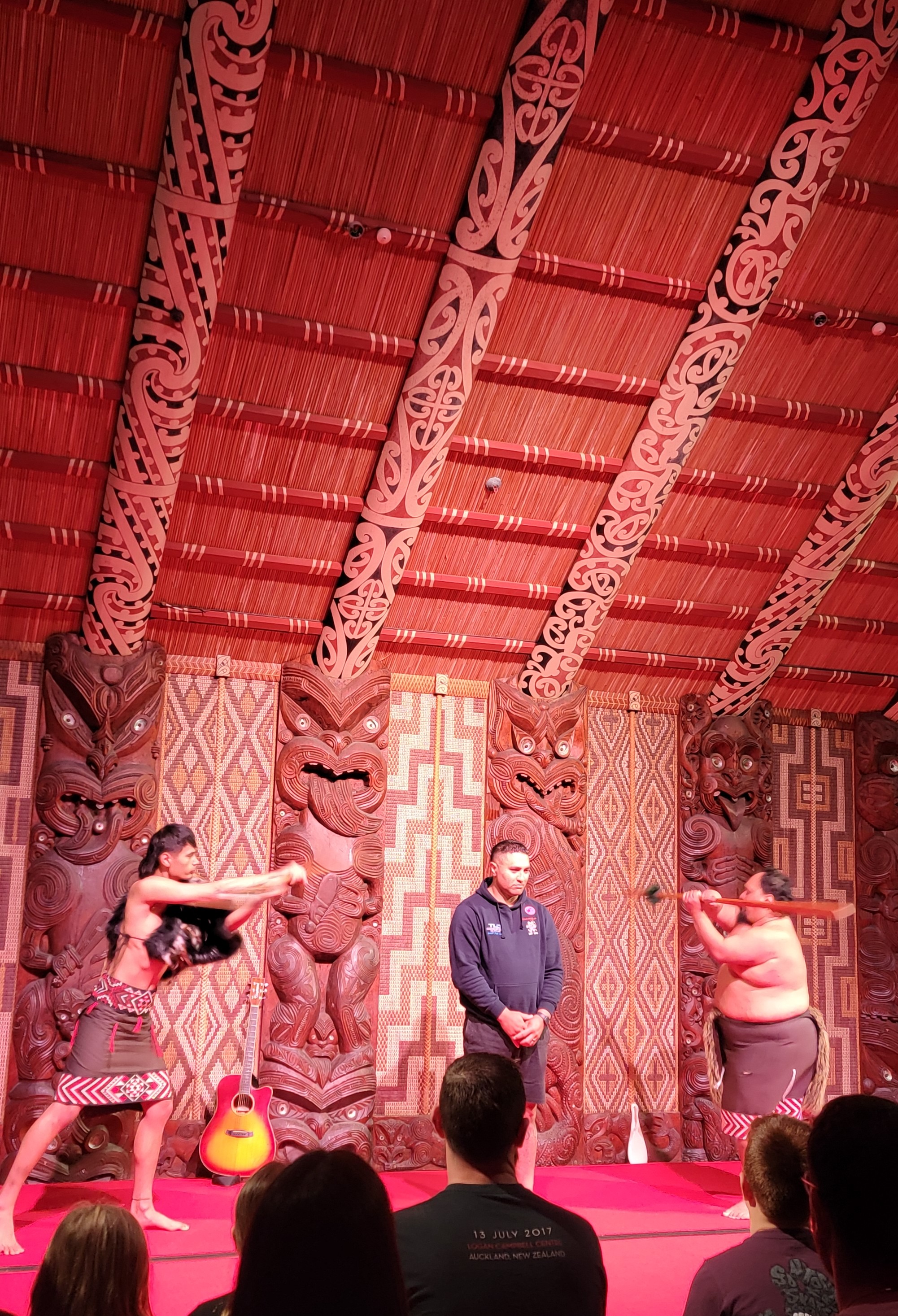

From here, we (and a gaggle of other tourists) were invited into the Māori marae, similar to what had happened when we had our “day in the Māori life” a week or so ago. The greeting was very similar, with a woman representing the “priestess” coming out, and a woman representing “us” introducing us to the priestess. Then, a “rangatira” was chosen from the audience, to represent our “whanau” (remember: pronounced FAH-now; extended family). He was presented a branch from one of the men, who came out and did what he hoped was an imposing “haka.” Interestingly, our Rangatira – Joe – was standing right in the middle, and was Māori! He picked up the branch the “peaceful” way, which we had learned about at our other marae experience, and then we were invited in the marae after taking off our shoes.

We were then treated to a singing/”dancing” show; however, the “dancing” was really based on stretches, warmups, and then practicing done with different weapons. There were three women and two men. As you can see, Rangatira Joe had to get up and stand very still while they practiced “around” him!

One thing we learned from our guide is that in 2008, the U.K. wanted to “re-ratify” the Treaty of Waitangi. However, as I’ve mentioned before, the English version and the Māori version were different. In the museum, they had copies of the original version, the Māori version, and what the English translation of the Māori version really means. When the Māori were gathered for the “ceremony,” the British just wanted them to sign “as they had before.” The British stated that this was just “ceremonial” for the anniversary of the signing. They said that Māori had already “agreed to” the English version. (They were all to sign the original English version of the Treaty this time.)

The head of the Māori delegation said two words: “Prove it.” The critical part? The Māori had signed the Māori version of the Treaty oh so many decades before – not the English version. Therefore – under English Common Law – the portions of the contract that were “different” would be “stricken”. . . which of course were the portions stating that they agreed Britain owned their land, the Queen could use Eminent Domain to do what she wanted, and the like (versus their version, which said the Queen was basically a rangatira who would protect them from harm and honor their land ownership and rangatira status; that their relationship would be a mutually beneficial partnership).

Many in our group had actually been to New Zealand before – and were very surprised at how much Māori language was included on everything – street signs, directions, historical markers, etc. We wondered if this change had happened around the time that it was “discovered” that “under English Common Law,” in actual fact, the portions that had been “mis-translated” in the Māori version (which the rangatira all signed) would not be binding.

One thing our guide had discussed with us was that the Māori had beaten the British via “trench warfare” (I discussed this yesterday). He said that they took the idea from eels – that when you hunt eels, they come out of a very small hole, but it digs down and ultimately there is a large compartment were all the eels are. He said that once the Māori and British were “friendly,” the Māori explained how they had dug the trench around their village and “tunnels” between the houses, etc. The guide stated that this is where the idea of trench warfare came from, that was incorporated into the British “war machine” from then on. Thank you, eels. :-)

We went back to the museum – there was quite a moving section that had to do with all the Māori who had fought in various battles. Here is a video I sent to my “Whanau.” Unfortunately I only captured 24 seconds, but you get the idea. It was an enormous crescent that was supposed to represent a lei. The black dots were Māori who served in the British Army in all wars from 1840 to World War I, the blue were those who served in World War I, the green World War II, and the grey all the wars after WW2. The red “dot” on any of those colors represents that the person had died in the war.

After leaving the museum, I think we grabbed lunch, but we were very soon in the van to head to the boat to take us out to the “Hole in the Rock.” This was where Lynn had wanted to leave her second one of Jim’s marbles, because he was a “water baby” and they hadn’t been able to get out there on their honeymoon. (If you like the idea of “cremarbles,” check out Public Glass.)

We passed “black rock” cliffs (basalt), a few beautiful beaches, and the Cape Bret lighthouse up on the hill and lighthouse keeper’s house below. The day before (when we were supposed to take this trip), the waves/water were awful, but luckily the day was beautiful.

On the way back, the boat docked at Otehei Bay. I pointed out as we were coming in what looked like a floating yurt – and it was! HERE is their Instagram :-) Otehei Bay was a beautiful area, where you can stay in a small cabin overnight. They have one restaurant – no WiFi as you can see from the sign below! The oddest thing was that they had no rubbish bins. When Don asked about it, he was told that stopped people from throwing things away . . . UNLESS they just left their debris on the beach, where the staff had to go pick it up. (??) Unclear on the concept?? It was low tide, and you could see what “used to be” oysters – that the birds had eaten up!!

We headed back to Russell when the ferry returned, and had our Farewell Dinner at the Duke of Marlborough (remember the story from our Russell tour?) This was one of the fishies in the bar:

Late day – time to pack for an early departure back to the Auckland airport! (Quite a ways away)

If you want $100 off, call OAT at 1-800-955-1925 and request a catalog, tell them you were referred by Sandy Shepard, customer number 3087257, and get $100 off your first trip!